Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"F-22" redirects here. For other uses, see F22 (disambiguation).

| F-22 Raptor | |

|---|---|

| |

| A USAF F-22A Raptor flies in a training mission duringRed Flag 2012 over Nevada. | |

| Role | Stealth air superiority fighter |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Boeing Defense, Space & Security |

| First flight | 7 September 1997[1] |

| Introduction | 15 December 2005 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary user | United States Air Force |

| Produced | F-22: 1996–2011[2] |

| Number built | 195 (eight test and 187 operational) aircraft[2] |

| Program cost | US$66.7 billion[3] |

| Unit cost | US$150 million (flyaway cost for FY2009)[4] |

| Developed from | Lockheed YF-22 |

| Developed into | Lockheed Martin X-44 MANTA Lockheed Martin FB-22 |

The Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor is a single-seat, twin-engine fifth-generation supersonic supermaneuverable fighter aircraft that uses stealth technology. It was designed primarily as an air superiority fighter, but has additional capabilities that include ground attack, electronic warfare, andsignals intelligence roles.[5] Lockheed Martin Aeronautics is the prime contractor and is responsible for the majority of the airframe, weapon systems and final assembly of the F-22. Program partner Boeing Defense, Space & Security provides the wings, aft fuselage, avionics integration, and training systems.

The aircraft was variously designated F-22 and F/A-22 prior to formally entering service in December 2005 as the F-22A. Despite a protracted development, the United States Air Force considers the F-22 a critical component of their tactical air power, and claims that the aircraft is unmatched by any known or projected fighter.[6] Lockheed Martin claims that the Raptor's combination of stealth, speed, agility, precision and situational awareness, combined with air-to-air and air-to-ground combat capabilities, makes it the best overall fighter in the world today.[7] Air Chief Marshal Angus Houston, former Chief of the Australian Defence Force, said in 2004 that the "F-22 will be the most outstanding fighter plane ever built."[8]

The high cost of the aircraft, a lack of clear air-to-air missions because of delays in Russian and Chinese fighter programs, a ban on exports, and development of the cheaper and more versatile F-35 led to the end of F-22 production.[N 1] A final procurement tally of 187 operational aircraft was established in 2009;[10] the final F-22 rolled off the assembly line on 13 December 2011 during a ceremony at Dobbins Air Reserve Base.[11]

Starting in 2010, the F-22 was plagued by oxygen system problems which contributed to one crash and death of a pilot. In 2011 the fleet was grounded for four months before resuming flight, reports of oxygen issues persisted.[12]In July 2012, the Air Force announced that the hypoxia-like symptoms experienced were caused by a faulty valve in the pilots' pressure vest; the valve was replaced and the filtration system also changed.

Contents

[hide]Development[edit]

Origins[edit]

Main articles: Advanced Tactical Fighter and Lockheed YF-22

In 1981 the U.S. Air Force developed a requirement for an Advanced Tactical Fighter (ATF) as a new air superiority fighter to replace the F-15 Eagle and F-16 Fighting Falcon. This was influenced by the emerging worldwide threats, including development and proliferation of Soviet Su-27 "Flanker"- and MiG-29 "Fulcrum"-class fighter aircraft. It would take advantage of the new technologies in fighter design on the horizon, including composite materials, lightweight alloys, advanced flight-control systems, more powerful propulsion systems, andstealth technology. A request for proposals (RFP) was issued in July 1986 and two contractor teams, Lockheed/Boeing/General Dynamics and Northrop/McDonnell Douglas, were selected on 31 October 1986 to undertake a 50-month demonstration phase, culminating in the flight test of two prototypes, the YF-22 and the YF-23.[13][14][15]

Each design team produced two prototypes, one for each of the two engine options. The Lockheed-led team chose to employ thrust vectoring for enhanced pitch performance, a useful capability in dogfights. The ATF's increasing weight and cost drove out some features during development. A dedicated infra-red search and track (IRST) system was downgraded from multi-color to single color and then deleted, the side-looking radars were deleted and the ejection seat requirement was downgraded from a fresh design to the existing McDonnell Douglas ACES II.[16]

After a 90-day flight test validation of the prototype air vehicles, on 23 April 1991, Secretary of the U.S. Air Force Donald Riceannounced the YF-22 was the winner of the ATF competition.[17] The YF-23 design was more stealthy and faster, but the YF-22 was more agile.[18] The aviation press speculated that the YF-22 was also more adaptable to the Navy's Navalized Advanced Tactical Fighter (NATF), but by 1992, the U.S. Navy had abandoned NATF.[19] In 1991, the USAF planned to buy 650 aircraft.[20]

Production and procurement[edit]

On 9 April 1997, the production F-22 model was unveiled at Lockheed Georgia Co.,Marietta, Georgia. It first flew on 7 September 1997. The first production F-22 was delivered to Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada, on 7 January 2003.[21] In 2006, the Raptor's development team, composed of Lockheed Martin and over 1,000 other companies, plus the United States Air Force, won the Collier Trophy, American aviation's most prestigious award.[22] In 2006, the USAF sought to acquire 381 F-22s, to be divided among seven active duty combat squadrons and three integrated Air Force Reserve Command and Air National Guard squadrons.[23]

Several design changes were made from the YF-22 for production. The swept-back angle on the wing's leading edge was decreased from 48° to 42°, while the vertical stabilizer area was decreased by 20%. To improve pilot visibility, the canopy was moved forward 7 inches (178 mm), and the engine intakes moved rearward 14 inches (356 mm). The shapes of the wing and stabilator trailing edges were refined to improve aerodynamics, strength, and stealth characteristics.[24][25] Also, the vertical stabilizer was shifted rearward.[26] During development, the aircraft increased considerably in weight, reducing its range and aerodynamic performance, despite several systems being removed from the design.[27]

F-22 production was split up over many subcontractors across 46 states, in a strategy to increase Congressional support;[28][29] this production split, along with several technologies employed, was likely responsible for increased costs and delays.[30] Many capabilities were deferred to post-service upgrades, reducing the initial cost but increasing total cost.[31] Each aircraft built required "1,000 subcontractors and suppliers and 95,000 workers".[32] The F-22 was in production for 15 years, at a rate of roughly two per month.[33]

The United States Air Force originally planned to order 750 ATFs at a cost of $26.2 billion,[34] with production beginning in 1994; however, the 1990 Major Aircraft Review led by Defense Secretary Dick Cheney altered the plan to 648 aircraft beginning in 1996. In 1994, the number was cut to 438 aircraft to enter service in 2003-2004; a 1997 Department of Defense report put the purchase at 339.[34] In 2003, the Air Force state the existing congressional cost cap limited the purchase to 277. In December 2004, the Department of Defense reduced funding so only 183 aircraft could be bought.[35] The Pentagon stated the reduction to 183 fighters would save $15 billion but raise the cost of each aircraft; this was implemented in the form of a multi-year procurement plan, which allowed for further orders later. The total cost of the program by 2006 was $62 billion.[23]

In April 2006, the cost of the F-22 was assessed by the Government Accountability Office to be $361 million per aircraft. By April 2006, $28 billion had been invested in F-22 development and testing; while the Unit Procurement Cost was estimated at $177.6 million in 2006, based on a production run of 181 aircraft.[36][37] It was estimated by the end of production, $34 billion will have been spent on procurement, resulting in a total program cost of $62 billion, around $339 million per aircraft. The incremental cost for an additional F-22 was estimated at about $138 million.[23][38] In March 2012, the GAO increased the estimated cost to $412 million per aircraft.[39][40] On 31 July 2007, Lockheed Martin received a $7.3 billion contract for 60 F-22s.[41][42]The contract brought the number of F-22s on order to 183 and extended production through 2011.[41]

Ban on exports[edit]

The F-22 cannot be exported under American federal law.[43] Customers for U.S. fighters are either acquiring earlier designs such as the McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle, General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon, and Boeing F/A-18E/F Super Hornet, or shall acquire the upcoming Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II (Joint Strike Fighter), which contains technology from the F-22 but is designed to be cheaper, more flexible, and available for export.[44] On 27 September 2006, Congress upheld the ban on foreign F-22 sales.[45]However, the 2010 defense authorization bill included provisions requiring the DoD to prepare a report on the costs and feasibility for an F-22 export variant, and another report on the impact of F-22 export sales on the U.S. aerospace industry.[46][47]

Some Australian politicians and defense commentators proposed that Australia should purchase F-22s instead of the F-35.[48][49] In 2006, Kim Beazley, leader of the Australian Labor Party supported this proposal on the grounds that the F-22 is a proven, highly capable aircraft, while the F-35 is still under development.[50] However, Australia's Howard government ruled out purchase of the F-22, as its release for export is unlikely, and lacks sufficient ground/maritime strike capacity.[51] The following year, the newly elected Rudd government ordered a review of plans to procure the F-35 and F/A-18E/F Super Hornet, including an evaluation of the F-22's suitability. The then Defence Minister Joel Fitzgibbon stated: "I intend to pursue American politicians for access to the Raptor".[52] In February 2008, U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates said he had no objection to F-22 sales to Australia.[53] However, the RAAF found that the "F-22 Raptor cannot perform the strike or close air support roles planned for the JSF."[54]

"The IAF would be happy to equip itself with 24 F-22s, but the problem at this time is the U.S. refusal to sell the aircraft, and its $200 million price tag."

Israeli Air Force (IAF) chief procurement officer Brigadier-General Ze'ev Snir.[55]

The Japanese government showed interest in the F-22 for its Replacement-Fighter program.[56]However, a sale would need approval from the Pentagon, State Department and Congress. It was stated that the F-22 would decrease the number of fighters needed by the Japan Air Self-Defense Force (JASDF), reducing engineering and staffing costs. In August 2009, it was reported that the F-22 would require increases to the military budget beyond the historical 1 percent of GDP.[57] In June 2009, Japanese Defense Minister Yasukazu Hamada said Japan still sought the F-22.[58]

Thomas Crimmins of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy speculated in 2009 that the F-22 could be a strong diplomatic tool for Israel, strengthening the capability to strike Iranian nuclear facilities.[59] Crimmins also claimed that the F-22 may be the only aircraft able to evade the Russian S-300 air defense system, which may be sold to Iran;[60] Lockheed Martin has stated that the F-35 can handle the S-300.[61]

Production termination[edit]

In 2006, David M. Walker, Comptroller General of the United States at the time, found that "the DoD has not demonstrated the need or value for making further investments in the F-22A program."[62] In 2007, several U.S. Senators demanded Deputy Secretary of Defense Gordon R. England release three government reports supporting additional F-22s beyond the planned 183 jets.[63] In January 2008, the Pentagon announced that it would ask Congress to fund additional F-22s to replace other aircraft lost in combat, and proposed that $497 million that would have been used to shut down the F-22 line be instead used to buy four extra F-22s;[64] the funds earmarked for line shutdown were later redirected to repair work on the F-15 fleet.[65]

On 24 September 2008, Congress passed a defense spending bill funding continued production of the F-22.[66] On 12 November 2008, the Pentagon released $50 million of the $140 million approved by Congress to buy parts for an additional four aircraft, thus leaving the Raptor program in the hands of the incoming Obama Administration.[67] On 6 April 2009, Secretary of Defense Gates called for the phasing out of F-22 production in fiscal year 2011, leaving the USAF with a production run of 187 fighters, minus losses.[10] On 17 June 2009 the House Armed Services Committee inserted $368.8 million in the budget towards a further 12 F-22s in FY 2011.[68]

On 9 July 2009, General James Cartwright, Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, explained to the U.S. Senate Committee on Armed Services his reasons for supporting termination of F-22 production. He stated that fifth-generation fighters need to be proliferated to all three services by shifting resources to the multirole F-35. He noted that commanders had concerns regarding electronic warfare (EW) capabilities, and that keeping the F/A-18 production line "hot" offered a fallback option to the F-35 in the EA-18G Growler.[69] By mid-2009, leaked reports from the Pentagon to The Washington Post stated that the F-22 had suffered from poor reliability and availability, specifically an average of one critical failure for every 1.7 flying hours and 30 hours of maintenance per flight hour;[44] the USAF disputed the accuracy of this figure.[70]

On 21 July 2009, President Obama threatened to veto further production.[71][72] On 21 July 2009, the Senate voted in favor of ending F-22 production. Secretary Gates said that the decision was taken in light of the F-35's capabilities.[73] On 29 July 2009, the Air National Guard's director asked for "60 to 70" F-22s for air sovereignty missions, noting that these could lack capabilities such as ground attack.[74] On 30 July 2009, the House agreed to remove funds for an additional 12 aircraft and abide by the 187 cap.[75] In mid-2010, Gates reduced the F-22 requirement from 243 to 187 aircraft, by lowering the preparations for two major regional conflicts to one.[76]

"The Pentagon cannot continue with business as usual when it comes to the F-22 or any other program in excess of our needs."

In 2010, RAND estimated that to restart production and build an additional 75 F-22s would cost a total of $17 billion or $227 million per aircraft; shutting down and restarting production two years later would add $54 million to the average cost.[79] Lockheed Martin stated that restarting the production line itself would cost about $200 million.[80] The RAND paper was produced as part of a USAF study to determine the costs of retaining F-22 tooling for a future Service Life Extension Program (SLEP).[81]Production tooling will be documented in illustrated electronic manuals stored at the Sierra Army Depot.[82] Retained tooling will produce additional components; due to the limited production run there are no reserve aircraft, leading to considerable care during maintenance.[83]

Russian and Chinese fighter developments have fueled concern; in 2009, General John Corley, head of Air Combat Command, stated in a letter written to a senator that a fleet of 187 F-22s would be inadequate, but Gates dismissed this concern.[84] On 8 January 2011, Gates clarified that Chinese fifth-generation fighter developments had been accounted when the number of F-22s was set, and that the United States would have a considerable advantage in stealth aircraft in 2025, even with F-35 delays.[85] In December 2011, the 195th and final F-22 was completed (out of 8 test and 187 combat aircraft produced).[86]

Upgrades[edit]

The first combat-capable Block 3.0 aircraft was first flown on 5 January 2001.[87] In 2009, Increment 3.1 began testing, providing a basic ground-attack capability through synthetic-aperture radar mapping and radio emitter direction finding, electronic attack and theGBU-39 Small Diameter Bomb.[88] The Increment 3.1 Modification Team with the 412th Test Wing received the Chief of Staff Team Excellence Award for upgrading 149 Raptors.[89][90] The first upgraded aircraft was delivered in 2012.[91]

Increment 3.2 was to add an improved SDB capability, an automatic ground collision avoidance system and enable use of the AIM-9X Sidewinder and AIM-120D AMRAAMmissiles.[92] In 2009, three business jets were equipped with the Battlefield Airborne Communications Node (BACN) for communicating between the F-22 and other platforms prior to the Multifunction Advanced Data Link (MADL).[93] In March 2010, the USAF accelerated software portions of Increment 3.2 to be completed in FY 2013.[94] Applying the 3.2 upgrade to 183 aircraft was estimated to cost $8 billion, officials stated that this to be funded via the early retirement of legacy fighters.[95][96]

In January 2011, the USAF opened the Raptor enhancement, development and integration (REDI) contract to bidders, with a $16 billion budget.[97] In November 2011, Lockheed Martin's upgrade contract was increased by $1.4 billion to a maximum value of $7.4 billion.[98][99] Of the $11.7 billion allocated for upgrades, almost $2 billion was for structural repairs and to increase the fleet's availability rate from 55.5% to 70.6% by 2015.[100] In 2010, Lockheed Martin proposed adding F-35 technologies,[101] such as durable stealth coatings.[102] Elements such as MADL are delayed until the F-35 program is completed.[103]

Increment 3.2A in 2014 focuses on electronic warfare, communications and identification; Increment 3.2B in 2017 involves the AIM-9X and AIM-120D missiles.[104] Lockheed Martin is developing the AN/AAR-56 Missile Launch Detector (MLD) to provide Infrared Search and Track functionality, similar to the F-35's SAIRST.[105] The F-22 is unable to utilize off-boresight and lock-on after launch missile functions;[106] a planned evaluation of the Visionix Scorpion helmet-mounted cueing system (HMCS), capable of off-boresight missile launches,[107] was canceled due to sequestration in 2013.[108] By 2012, the update schedule had slipped seven years because of "requirements and funding instability".[109]

In February 2013, Lockheed's upgrade contract was modified to include the 3.2B features, bringing the total upgrade cost to $6.9 billion; work is expected to be completed by 2023. Increment 3.2C, which may include the adoption of an open avionics platform and air traffic control updates, was redesignated as Increment 3.3.[110][111] In 2016, the F-22 fleet shall be upgraded to 36 Block 20 training aircraft and 149 Block 30/35 operational aircraft.

While no definitive, single cause was found for the frequent oxygen deprivation issues responsible for several incidents, including a fatal crash, the F-22 will be upgraded with a backup oxygen system, software upgrades and oxygen sensors to normal operatons in spite of the problem.[112] In 2013, the faulty flight vest valves were replaced and altitude restrictions lifted; distance restrictions will be lifted once a backup oxygen system is installed.[113]

The F-22 was designed for a lifespan of 30 years and 8000 flight hours, with a $100 million "structures retrofit program".[114]Investigations are being made for upgrades to extend their useful lives further.[115] In the long term, the F-22 is expected to eventually be replaced by the Next Generation Air Dominance program.[116]

Design[edit]

Characteristics[edit]

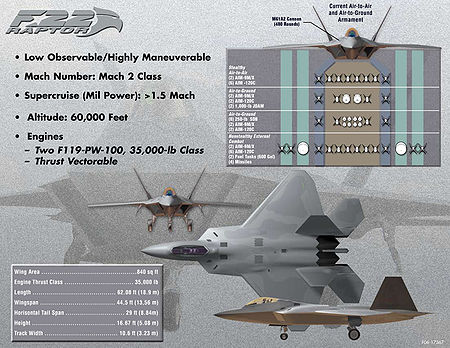

The F-22 Raptor is a fifth generation fighter that is considered a fourth-generation stealth aircraft by the USAF.[117] Its dual afterburning Pratt & Whitney F119-PW-100 turbofansincorporate pitch axis thrust vectoring, with a range of ±20 degrees. The maximum thrust isclassified, though most sources place it at about 35,000 lbf (156 kN) per engine.[118]Maximum speed, without external weapons, is estimated to be Mach 1.82 in supercruisemode,[119] as demonstrated by General John P. Jumper, former U.S. Air Force Chief of Staff, when his F-22 exceeded Mach 1.7 without afterburners on 13 January 2005.[120] With afterburners, it is "greater than Mach 2.0" (greater than 1,327 mph, 2,135 km/h). Former Lockheed chief test pilot Paul Metz stated that the Raptor has a fixed inlet, as opposed tovariable intake ramps, and that the F-22 has a greater climb rate than the F-15.[121] The Air Force claims that the Raptor cannot be matched by any known or projected fighter types,[6]and Lockheed Martin claims: "the F-22 is the only aircraft that blends supercruise speed, super-agility, stealth and sensor fusion into a single air dominance platform."[122]

To withstand both stress and heat factors, the F-22 makes extensive use of materials such as high-strength titanium and composites to a greater degree than previous fighters, at 39% and 24% respectively.[123] The use of internal weapons bays allows the aircraft to maintain a comparatively higher performance while carrying a heavy payload over most aircraft due to a lack of drag from external stores. It is one of only a few aircraft that can supercruise or sustain supersonic flight without the use of afterburners, which consume vastly more fuel; targets can be intercepted which subsonic aircraft would lack the speed to pursuit and an afterburner-dependent aircraft lack the fuel to reach.[124]

The F-22 is highly maneuverable, at both supersonic and subsonic speeds. It is extremelydeparture-resistant,[125] enabling it to remain controllable at extreme pilot inputs. The Raptor's thrust vectoring nozzles allow the aircraft to turn tightly, and perform extremely high alpha (angle of attack) maneuvers such as the Herbst maneuver (or J-turn), Pugachev's Cobra,[121] and the Kulbit.[121] The F-22 is also capable of maintaining a constant angle of attack of over 60° while maintaining some control of roll.[121][126] During June 2006 exercises in Alaska, F-22 pilots demonstrated the significant effect of cruise altitude on combat performance, attributing the altitude advantage as a major factor in achieving an unblemished kill ratio against other fighters.[127]

The F-22 has a unique combination of speed, altitude, agility, sensor fusion and stealth that work together for increased effectiveness. Altitude and advanced active and passive sensors allows targets to be spotted at considerable ranges; altitude and speed increases weapons reach. Altitude increases range from ground defenses, which increases stealth's effectiveness, combined with speed, defensive systems have less time to react to an F-22.[128][129][130][131]

Avionics[edit]

Key avionics include BAE Systems E&IS radar warning receiver (RWR) AN/ALR-94,[132] AN/AAR-56 Infra-Red and Ultra-Violet MAWS (Missile Approach Warning System) and the Northrop Grumman AN/APG-77 Active Electronically Scanned Array (AESA) radar. The RWR is a passive radar detector, more than 30 antennas are blended into the wings and fuselage for all-round coverage. Tom Burbage, former F-22 program head at Lockheed Martin, described it as "the most technically complex piece of equipment on the aircraft." The range of the RWR (250+ nmi) exceeds the radar's, allowing radar emissions to be limited for maximized stealth. The RWR can cue the radar to track approaching targets with a narrow beam ( down to 2° by 2° in azimuth and elevation).[133]

The AN/APG-77 radar, designed for air superiority and strike operations, features a low-observable, active-aperture, electronically-scanned array that can track multiple targets in any weather. Additionally, the radar emissions can be focused in an electronic-attack capability to overload enemy sensors.[134][135] The AN/APG-77 changes frequencies more than 1,000 times per second to lower interception probability. The radar has an estimated range of 125–150 miles, though planned upgrades will allow a range of 250 miles (400 km) or more in narrow beams.[127]

Radar information is processed by two Raytheon Common Integrated Processor (CIP)s; each CIP can process up to 10.5 billion instructions per second. Information from the radar, other sensors, and external systems is filtered by the CIP in a process known as sensor fusion; combining and processing data from multiple systems into a common view to prevent the pilot from being overwhelmed.[136] The F-22's software has some 1.7 millionlines of code, the majority involving processing radar data.[137] In 2007, tests by Northrop Grumman, Lockheed Martin, and L-3 Communications used the F-22's radar as a WiFi access point, able to transmit data at 548 megabits per second and receive at gigabit speed, far faster than the Link 16 system.[138]

The F-22 has a threat detection and identification capability comparative with the RC-135 Rivet Joint.[127] The F-22's stealth allows it to safely operate far closer to the battlefield, compensating for the reduced capability.[127] The F-22 is capable of functioning as a "mini-AWACS", however the radar is less powerful than those of dedicated platforms such as the E-3 Sentry.[121] The F-22 allows its pilot to designate targets for cooperating F-15s and F-16s, and determine whether two friendly aircraft are targeting the same aircraft.[121][127]This radar system can sometimes identify targets "many times quicker than the AWACS".[127] The radar is capable of high-bandwidth data transmission; conventional radio "chatter" can be reduced via these alternative means.[127] The IEEE-1394B data bus developed for the F-22 was derived from the commercial IEEE-1394 "FireWire" bus system.[139]

In 2009 former Navy Secretary John Lehman stated that "[the F-22s] are safe from cyberattack. No one in China knows how to program the '83 vintage IBM software that runs them."[140] Former Secretary of the USAF Michael Wynne blamed the use of the DoD'sAda for cost overruns and delays on many military projects, including the F-22.[141] Cyberattacks on Lockheed Martin's subcontractors have reportedly raised doubts about the security of the F-22's systems and combat-effectiveness.[142]

Cockpit[edit]

The F-22 features a glass cockpit with all-digital flight instruments.[143] The primary flight controls are a force-sensitive side-stick controller and a pair of throttles. The USAF initially wanted to implement direct voice input (DVI) controls; however this was judged to be too technically risky and abandoned.[144] The monochrome head-up display offers a wide field of view and serves as a primary flight instrument; information is also displayed upon six color liquid crystal display (LCD) panels.[143] The canopy's dimensions are approximately 140 inches long, 45 inches wide, and 27 inches tall (355 cm x 115 cm x 69 cm) and weighs 360 pounds.[145]

The F-22 has integrated radio functionality, the signal processing systems are virtualized rather than as a separate hardware module.[146] There has been several reports on the F-22's inability to communicate with other aircraft, and funding cuts have affected the development of the MADL data link.[147][148] Voice communication is possible, but not data transfer.[149]

The integrated control panel (ICP) is a keypad system for entering communications, navigation, and autopilot data. Two 3 in × 4 in (7.6 cm × 10.2 cm) up-front displays located around the ICP are used to display integrated caution advisory/warning data, communications, navigation and identification (CNI) data[150] and also serve as the stand-by flight instrumentation group and fuel quantity indicator.[151] The stand-by flight group displays an artificial horizon, for basic instrument meteorological conditions. The 8 in × 8 in (20 cm × 20 cm) primary multi-function display (PMFD) is located under the ICP, and is used for navigation and situation assessment.[151] Three 6.25 in × 6.25 in (15.9 cm × 15.9 cm) secondary multi-function displays are located around the PMFD for tactical information and stores management.[151]

The ejection seat is a version of the ACES II (Advanced Concept Ejection Seat) commonly used in USAF aircraft, with a center-mounted ejection control.[152] The F-22 has a complex life support system. Components include the on-board oxygen generation system (OBOGS), protective pilot garments, and a breathing regulator/anti-g valve controlling flow and pressure to the pilot's mask and garments. The protective garments are designed to protect against chemical/biological hazards and cold-water immersion, to counterg-forces and low pressure at high altitudes, and to provide thermal relief. It was developed under the Advanced Technology Anti-G Suit (ATAGS) project.[153] Suspicions regarding the performance of the OBOGS and life support equipment have been raised by several mishaps, including a fatal crash.[154]

Armament[edit]

The Raptor has three internal weapons bays: a large bay on the bottom of the fuselage, and two smaller bays on the sides of the fuselage, aft of the engine intakes.[155] It can carry six medium range missiles in the center bay and one short range missile in each side bay;[156]Four of the medium range missiles can be replaced with two bomb racks that can each carry one medium-size or four smaller bombs.[129] Carrying armaments internally maintains its stealth capability and lowers drag for higher top speeds and longer range. Missile launches require the bay doors to be open for less than a second, hydraulic arms push missiles clear of the aircraft; this is to reduce vulnerability to detection and to deploy missiles during high speed flight.[157]

The F-22 can also carry air-to-surface weapons such as bombs with Joint Direct Attack Munition(JDAM) guidance and the Small-Diameter Bomb, but cannot self-designate for laser-guided weapons.[158] Air-to-surface ordnance is limited to 2,000 lb (compared to 17,000 lb of F/A-18).[159] An internally-mounted M61A2 Vulcan 20 mm cannon is embedded the right wing root, the cannon is also covered by a door to maximize stealth.[160] During training, the F-22 has been able to close to cannon range in dogfights while avoiding detection.[121] The aircraft's radar can track cannon fire and display it on the pilot's heads up display.[161]

The Raptor's very high cruise speed and altitude increase the effective ranges of its munitions, the F-22 has a 40% greater employment range for air to air missiles than the F-35.[162] The USAF plans to procure the AIM-120D AMRAAM, reported to have a 50% increase in range compared to the AIM-120C. While specifics are classified, it is expected that JDAMs employed by F-22s will have twice or more the effective range of legacy platforms.[163] In testing, a Raptor dropped a 1,000 lb (450 kg) free-fall JDAM from 50,000 feet (15,000 m), while cruising at Mach 1.5, striking a moving target 24 miles (39 km) away.[164] This reach advantage was cited by Robert Gottliebsen as reason for Australia to favor an updated F-22 over the F-35.[165]

While the F-22 typically carries its weapons internally, the wings include four hardpoints, each rated to handle 5,000 lb (2,300 kg). Each hardpoint has a pylon that can carry a detachable 600 gallon fuel tank or a launcher holding two air-air missiles. However, the use of external stores has a detrimental effect on the F-22's stealth, maneuverability and speed. The two inner hardpoints are "plumbed" for external fuel tanks; the hardpoints can be jettisoned in flight so the fighter can maximize its stealth after exhausting external stores.[166]A stealth ordnance pod and pylon is being developed to carry additional weapons internally.[167]

Stealth[edit]

The stealth of the F-22 is due to a combination of factors, including the overall shape of the aircraft, the use of radar absorbent material, and attention to detail such as hinges and pilot helmets that could provide a radar return.[168] However, reduced radar cross section is one of five facets of presence reduction addressed in the designing of the F-22. The F-22 was designed to disguise its infrared emissions, reducing the threat of infrared homing ("heat seeking") surface-to-air or air-to-air missiles, including its flat thrust vectoring nozzles.[169] The aircraft was designed to be less visible to the naked eye; radio, heat and noise emissions are equally controlled.[168]

The F-22 reportedly relies less on maintenance-intensive radar absorbent coatings than previous stealth designs like the F-117. These materials are susceptible to adverse weather conditions.[170] Unlike the B-2, which requires climate-controlled hangars, the F-22 can undergo repairs on the flight line or in a normal hangar.[170] The F-22 features a Signature Assessment System which delivers warnings when the radar signature is degraded and has necessitated repair.[170] The exact radar cross section (RCS) remains classified; however, in 2009 Lockheed Martin released information indicating it to have a RCS (from certain angles) of −40 dBsm – the equivalent radar reflection of a "steel marble".[171] Effectively maintaining the stealth features can decrease the F-22's mission capable rate to 62–70%.[N 2]

The effectiveness of the stealth characteristics is difficult to gauge. The RCS value is a restrictive measurement of the aircraft's frontal or side area from the perspective of a static radar. When an aircraft maneuvers it exposes a completely different set of angles and surface area, potentially increasing visibility. Furthermore, stealth contouring and radar absorbent materials are chiefly effective against high-frequency radars, usually found on other aircraft. Low-frequency radars, employed by weather radars and ground warning stations, are alleged to be less affected by stealth technologies and are thus more capable as detection platforms.[173][174] Rebecca Grant states that while faint or fleeting radar contacts make defenders aware that a stealth aircraft is present, interception cannot be reliably vectored to attack the aircraft.[175]

The F-22 also includes measures designed to minimize its detection by infrared, including special paint and active cooling of leading edges to deal with the heat buildup encountered during supercruise flight.[176]

Operational history[edit]

Designation and testing[edit]

The YF-22 was originally given the unofficial name "Lightning II", after the World War II fighter P-38, by Lockheed, which persisted until the mid-1990s when the USAF officially named the aircraft "Raptor". The aircraft was also briefly dubbed "SuperStar" and "Rapier".[177] In September 2002, Air Force leaders changed the Raptor's designation to F/A-22, mimicking the Navy's McDonnell Douglas F/A-18 Hornet and intended to highlight a planned ground-attack capability amid debate over the aircraft's role and relevance. The F-22 designation was reinstated in December 2005, when the aircraft entered service.[6][178]

Flight testing began with Raptor 4001, the first engineering and manufacturing development (EMD) jet, in 1997. Nine F-22s would participate in the EMD and flight testing program.[179]Raptor 4001 was retired from flight testing in 2000 and subsequently sent to Wright-Patterson AFB for survivability testing, including live fire testing and battle damage repair training.[180] Several EMD F-22s have been used for testing upgrades, and also as maintenance trainers.[181]

In May 2006, a released report documented a problem with the F-22's forward titanium boom, caused by defective heat-treating. This made the boom on roughly the first 80 F-22s less ductile than specified and potentially shortened the part's life. Modifications and inspections were implemented to the booms to restore life expectancy.[182][183]

Entering service[edit]

On 15 December 2005, the USAF announced that the F-22 had achieved Initial Operational Capability (IOC).[184] During ExerciseNorthern Edge in Alaska in June 2006, in simulated combat exercises 12 F-22s of the 94th FS downed 108 adversaries with no losses.[23] In the exercises, the Raptor-led Blue Force amassed 241 kills against two losses in air-to-air combat; neither Blue Force loss was an F-22. During Red Flag 07-1 in February 2007, 14 F-22s of the 94th FS supported Blue Force strikes and undertook close air support sorties. Against superior numbers of Red Force Aggressor F-15s and F-16s, 6–8 F-22s maintained air dominance throughout. No sorties were missed because of maintenance or other failures, a single one F-22 was judged lost against the defeated opposing force.[N 3] F-22s also provided airborne electronic surveillance.[185]

Deployments[edit]

On 11 February 2007, while attempting its first overseas deployment to the Kadena Air Basein Okinawa, Japan, six F-22s of 27th Fighter Squadron flying from Hickam AFB, Hawaii, experienced multiple software-related system failures while crossing the International Date Line (or 180th meridian of longitude). The aircraft returned to Hawaii by following tanker aircraft. Within 48 hours, the error was resolved and the journey resumed.[186][187] On 22 November 2007, 90th Fighter Squadron performed the first F-22 NORAD interception of two Russian Tu-95MS 'Bear-H' bombers over Alaska.[188] Since then, F-22s have also escorted probing Tu-160 "Blackjack" strategic bombers.[189]

On 12 December 2007, General John D.W. Corley, USAF, Commander of Air Combat Command, officially declared the F-22s of the integrated active duty 1st Fighter Wing andVirginia Air National Guard 192d Fighter Wing fully operational, three years after the first aircraft arrived at Langley Air Force Base, Virginia.[190] This was followed by an Operational Readiness Inspection (ORI) of the integrated wing from 13 to 19 April 2008; it was rated "excellent" in all categories, with a simulated kill-ratio of 221–0.[191] The first pair of F-22s assigned to the 49th Fighter Wing became operational at Holloman Air Force Base, New Mexico, on 2 June 2008.[192]

In December 2007, Secretary of the Air Force Michael Wynne requested that the F-22 be deployed to the Middle East; Secretary of Defense Gates rejected this option.[193] Timesuggested part of the reason for it not being used in the 2011 military intervention in Libyamay have been its high unit cost.[194]

In 2008, prior to the USMC's Special Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force for Crisis Response, two F-22 pilots proposed that USAF form a rapid response airborne package of one C-17 to support four F-22s, able to set up and engage in combat within 24 hours.[195][196]

On 28 August 2008, an unmodified F-22 of the 411th Flight Test Squadron performed in the first ever air-to-air refueling of an aircraft using synthetic jet fuel as part of a wider USAF effort to qualify aircraft to use the fuel, a 50/50 mix of JP-8 and a Fischer-Tropsch process-produced, natural gas-based fuel.[197] In 2011, an F-22 made a supersonic flight on a 50% mixture of biofuel derived fromcamelina.[198]

In April 2012, F-22s were deployed to a base in the UAE, less than 200 miles from Iran;[199] the Iranian defense minister referred to the deployment as a security threat.[200] The F-22s returned to the U.S. in January 2013 after a nine-month deployment.[201] On 17 September 2013, the Air Force revealed that an F-22 had chased off an Iranian fighter over the Persian Gulf in March 2013. An IranianF-4 Phantom II had flown within 16 miles of an MQ-1 Predator flying off the Iranian coastline; the Raptor used its stealth to approach close to the underside of the Phantom before flying alongside. The confrontation is the first publicized engagement involving the F-22 and Iranian military forces.[202]

On 14 January 2013, 12 F-22s arrived at Kadena Air Base in Okinawa in the type's seventh deployment since 2007.[203] In early 2013, F-22s were involved in U.S.-South Korean military drills.[204]

Maintenance and training[edit]

In 2004, the F-22 had a mission ready rate of 62%, this rose to 70% in 2009 and was predicted to reach 85% as the fleet reached 100,000 flight hours.[205] Early on, the F-22 required more than 30 hours of maintenance per flight hour and a total cost per flight hour of $44,000; by 2008 it was reduced to 18.1, and 10.5 by 2009;[205] lower than the Pentagon's requirement of 12 maintenance hours per flight hour.[206] When introduced, the F-22 had a Mean Time Between Maintenance (MTBM) of 1.7 hours; by 2012 the figure was 3.2 hours, exceeding the requirement of 3.0 hours by 2010.[205] By 2013, the cost per flight hour had grown to $68,362, over three times as much as the F-16.[207]

Each aircraft requires a month-long packaged maintenance plan (PMP) every 300 flight hours.[208] The stealth system, including its radar absorbing metallic skin, account for almost one third of maintenance.[205] Many components require custom hand-fitting and are not interchangeable.[44] Against a required life expectancy of 800 hours, the original canopy only averaged 331 hours;[44] thus the canopy was redesigned to successfully meet the 800 hour target.[205]

In January 2007, it was reported that the F-22 maintained a 97% sortie rate (flying 102 out of 105 tasked sorties) while amassing a 144-to-zero kill ratio during "Northern Edge" air-to-air exercises in Alaska. Lieutenant Colonel Wade Tolliver, squadron commander of the 27th Fighter Squadron, commented: "the stealth coatings are not as fragile as they were in earlier stealth aircraft. It isn't damaged by a rain storm and it can stand the wear and tear of combat without degradation."[170] However, rain caused "shorts and failures in sophisticated electrical components" when F-22s were posted to Guam.[209]

In its 2012 budget request, the USAF cut F-22 flight training hours by one-third to reduce operating costs;[210] however F-22 was to continue to operate as the only USAF solo aircraft demonstrator.[211] DoD budget cuts led to F-22 demonstration flights being halted in 2013 to release funds for combat aircraft.[212] In 2012, it was reported that the F-22's maintenance demands have increased as the fleet aged, maintaining the stealth coatings is particularly demanding.[213][214]

Operational issues[edit]

Operational issues have been experienced, some have caused fleet-wide groundings. Critically, pilots have experienced a decreased mental status, including losing consciousness. There were reports of instances of pilots found to have a decreased level of alertness and/or memory loss after landing.[215] F-22 pilots have experienced lingering respiratory problems and a chronic cough; other symptoms include irritability, emotional lability and neurologic changes.[215] A number of possible causative factors were investigated, including possible exposure to noxious chemical agents from the respiratory tubing, pressure suit malfunction, side effects from oxygen delivery at greater-than-atmospheric concentrations, and oxygen supply disruptions. Other issues include minor mechanical problems and navigational software failures.[216]

In 2005, the Raptor Aeromedical Working Group, a USAF expert panel, recommended several changes to deal with the oxygen supply issues.[217] In October 2011, Lockheed Martin was awarded a $24M contract to investigate the breathing difficulties.[218] In July 2012, the Pentagon concluded that a pressure valve on flight vests worn during high-altitude flights and a carbon air filter were likely sources of at least some hypoxia-like symptoms. Long-distance flights were resumed, but were limited to lower altitudes until corrections had been made. The carbon filters were changed to a different model to reduce lung exposure to carbon particulates.[219][220] The breathing regulator/anti-G (BRAG) valve, used to inflate the pilot's vest during high G maneuvers, was found to be defective, inflating the vest at unintended intervals, causing the pilot to shallow-breath.[221] The on-board oxygen generating system (OBOGS) also unexpectedly reduced oxygen levels during high-G maneuvers.[222] In late 2012, Lockheed was awarded contracts to install a supplemental automatic oxygen backup system, in addition to the primary and manual backup.[223] Changes recommended by the Raptor Aeromedical Working Group in 2005 received further consideration in 2012;[224] the USAF reportedly considered installing EEG brain wave monitors on the pilot's helmets for inflight monitoring.[225][226]

New backup oxygen generators and filters have been installed on the aircraft. The coughing symptoms have been attributed to acceleration atelectasis, which may be exacerbated by the F-22's high performance, there is no present solution to the condition. The presence of toxins and particles in some ground crew was been deemed to be unrelated.[227] On 4 April 2013, the distance and altitude flight restrictions were lifted after the F-22 Combined Test Force and 412th Aerospace Medicine Squadron determined that breathing restrictions on the pilot were responsible as opposed to an issue with the oxygen provided.[228][229][230]

Variants[edit]

- YF-22A – pre-production version used for ATF testing and evaluation. Two were built.

- F-22A – single-seat production version. Was designated "F/A-22A" in early 2000s.

- F-22B – planned two-seat variant, but was dropped in 1996 to save development costs.[231]

- Naval F-22 variant – a carrier-borne variant of the F-22 with swing-wings for the U.S. Navy's Navy Advanced Tactical Fighter(NATF) program to replace the F-14 Tomcat. Program was canceled in 1993.[231] Former SoAF Donald Rice has called the possibility of the naval variant the deciding factor for his choice of the YF-22 over the YF-23.[232]

Derivatives[edit]

The FB-22 was a proposed medium-range bomber for the USAF.[233] The FB-22 was projected to carry up to 30 Small Diameter Bombs to about twice the range of the F-22A, while maintaining the F-22's stealth and supersonic speed.[234] However, the FB-22 in its planned form appears to have been canceled with the 2006 Quadrennial Defense Review and subsequent developments, in lieu of a larger subsonic bomber with a much greater range.[235][236]

The X-44 MANTA, or multi-axis, no-tail aircraft, was a planned experimental aircraft based on the F-22 with enhanced thrust vectoringcontrols and no aerodynamic surface backup.[237] The aircraft was to be solely controlled by thrust vectoring, without featuring any rudders, ailerons, or elevators. Funding for this program was halted in 2000.[238]

Operators[edit]

The United States Air Force is the only operator of the F-22. It ordered 187 aircraft with the last received by early Q2 2012.[80][239] By November 2012, crashes had reduced the total to 182.[240] It is operated by the following commands:

- Air Combat Command

- 1st Fighter Wing, Langley AFB, Virginia

- 27th Fighter Squadron – The first combat F-22 squadron. Began conversion in December 2005.[241]

- 94th Fighter Squadron

- 49th Fighter Wing, Holloman AFB, New Mexico[242]

- 53d Wing, Eglin AFB, Florida

- 57th Wing, Nellis AFB, Nevada

- 325th Fighter Wing, Tyndall AFB, Florida

- 43d Fighter Squadron – The first squadron to operate the F-22 and continues to serve as the Formal Training Unit.[245] Known as the "Hornets", the 43d was re-activated at Tyndall in 2002.

- 95th Fighter Squadron [246]

- 1st Fighter Wing, Langley AFB, Virginia

- Air Force Materiel Command

- 412th Test Wing, Edwards AFB, California

- 411th Flight Test Squadron – Conducted competition between YF-22 and YF-23from 1989–1991. Continues to conduct flight test on F-22 armaments and upgrades.

- 412th Test Wing, Edwards AFB, California

- Pacific Air Forces

- 3d Wing, Elmendorf AFB, Alaska

- 15th Wing, Hickam AFB, Hawaii

- 19th Fighter Squadron – Active Associate squadron to the 199th Fighter Squadron (Hawaii Air National Guard). [N 4]

- Air National Guard

- 192d Fighter Wing, Langley AFB, Virginia

- 149th Fighter Squadron, Virginia Air National Guard – Associate ANG squadron to the 1st Fighter Wing (Air Combat Command).

- 154th Wing, Hickam AFB, Hawaii[250]

- 192d Fighter Wing, Langley AFB, Virginia

- Air Force Reserve Command

- 44th Fighter Group, Holloman AFB, New Mexico[251]

- 301st Fighter Squadron – Associate AFRC squadron to the 49th Wing (Air Combat Command).

- 477th Fighter Group, Elmendorf AFB, Alaska

- 302d Fighter Squadron – Associate AFRC squadron to the 3d Wing (Pacific Air Forces).

- 44th Fighter Group, Holloman AFB, New Mexico[251]

Accidents[edit]

In April 1992, the second YF-22 crashed while landing at Edwards Air Force Base, California. The test pilot, Tom Morgenfeld, escaped without injury. The cause of the crash was found to be a flight control software error that failed to prevent a pilot-induced oscillation.[252]

The first crash of a production F-22 occurred during takeoff at Nellis Air Force Base on 20 December 2004, in which the pilot ejected safely before impact.[253][254] The crash investigation revealed that a brief interruption in power during an engine shutdown prior to flight caused a malfunction in the flight-control system;[255] consequently the aircraft design was corrected to avoid the problem. All F-22s were grounded after the crash; operations resumed following a review.[256]

On 25 March 2009, an EMD F-22 crashed 35 miles (56 km) northeast of Edwards Air Force Base during a test flight,[257] resulting in the death of Lockheed test pilot David P. Cooley.[44][258] An Air Force Materiel Command investigation found that Cooley momentarily lost consciousness during a high-G maneuver, then ejected when he found himself too low to recover. Cooley was killed during ejection by blunt-force trauma from the aircraft's speed and the windblast. The investigation found no issues with the F-22's design.[259][260]

On 16 November 2010, an F-22, based at Elmendorf, Alaska, crashed, killing the pilot, Captain Jeffrey Haney.[261] The F-22 fleet was restricted to flying below 25,000 feet, before being grounded while the accident was investigated.[262] The accident was attributed to a bleed air system malfunction following the detection of an engine overheat condition, this shut down the Environmental Control System (ECS) and On-Board Oxygen Generating System (OBOGS).[263][264] The accident review board ruled the pilot was to blame, as he did not react properly and did not engage the emergency oxygen system.[264][265] General Schwartz called the Pentagon Office of the Inspector General investigation of the report "routine",[266][267] and rejected pilot blame.[268] The pilot's widow sued, claiming the aircraft has defective equipment;[269] the manufacturers later reached a settlement.[270] In response to the investigation results, the engagement handle for the emergency oxygen system was redesigned; the emergency oxygen system should engage automatically when OBOGS is shut down due to engine failure.[271] On 11 February 2013, the DoD's Inspector General released its report, which found that the USAF had erred in assigning blame to Haney for the crash, stating that conclusions were contradictory, incomplete, or "not supported by facts"; the USAF stated that it stood by its conclusions.[272][273]

During a training mission, an F-22 crashed to the east of Tyndall Air Force Base, on 15 November 2012. The pilot ejected safely and no injuries were reported on the ground.[274][275] The investigation determined that a "chafed" electrical wire ignited the fluid in a hydraulic line, causing a fire that damaged the flight controls.[276]

Aircraft on display[edit]

EMD F-22A 91-4003 is on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force.[277]

Specifications[edit]

Data from USAF,[6] F-22 Raptor Team web site,[278] Manufacturers' data,[279][280] Aviation Week,[127] and Journal of Electronic Defense,[133]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 62 ft 1 in (18.90 m)

- Wingspan: 44 ft 6 in (13.56 m)

- Height: 16 ft 8 in (5.08 m)

- Wing area: 840 ft² (78.04 m²)

- Airfoil: NACA 64A?05.92 root, NACA 64A?04.29 tip

- Empty weight: 43,340 lb (19,700 kg[6][279])

- Loaded weight: 64,460 lb (29,300 kg[N 5])

- Max. takeoff weight: 83,500 lb (38,000 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × Pratt & Whitney F119-PW-100 Pitch Thrust vectoring turbofans

- Dry thrust: 23,500 lb[282] (104 kN) each

- Thrust with afterburner: 35,000+ lb[6][282] (156+ kN) each

- Fuel capacity: 18,000 lb (8,200 kg) internally,[6][279] or 26,000 lb (11,900 kg) with two external fuel tanks.[6][279] About 3,050 gal or 20,333 lb JP-8 (without additions) internally.[283]

Performance

- Maximum speed: **At altitude: Mach 2.25 (1,500 mph, 2,410 km/h) [estimated][119]

- Supercruise: Mach 1.82 (1,220 mph, 1,963 km/h)[119]

- Range: >1,600 nmi (1,840 mi, 2,960 km)with 2 external fuel tanks

- Combat radius: 410 nmi (with 100 nmi in supercruise)[278] (471 mi, 759 km)

- Ferry range: 2,000 mi (1,738 nmi, 3,219 km)

- Service ceiling: >65,000 ft [284] (19,812 m)

- Wing loading: 77 lb/ft² (375 kg/m²)

- Thrust/weight: 1.09 (1.26 with loaded weight & 50% fuel)

- Maximum design g-load: -3.0/+9.0 g[119]

Armament

- Guns: 1× 20 mm (0.787 in) M61A2 Vulcan 6-barreled Gatling cannon in right wing root, 480 rounds

- Air to air loadout:

- Air to ground loadout:

- 2× AIM-120 AMRAAM and

- 2× AIM-9 Sidewinder for self-protection, and one of the following:

- 2× 1,000 lb (450 kg) JDAM or

- 8× 250 lb (110 kg) GBU-39 Small Diameter Bombs

- Hardpoints: 4× under-wing pylon stations can be fitted to carry 600 U.S. gallon drop tanks or weapons, each with a capacity of 5,000 lb (2,268 kg).[285]

Avionics

- RWR (Radar warning receiver): 250 nmi (463 km) or more[133]

- Radar: 125–150 miles (200–240 km) against 1 m2 (11 sq ft) targets (estimated range)[127]

- Chemring MJU-39/40 flares for protection against IR missiles.[286]

Notable appearances in media[edit]

Main article: F-22 Raptor in fiction

See also[edit]

- Related development

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Related lists

- List of fighter aircraft

- List of Lockheed aircraft

- List of active United States military aircraft

- List of megaprojects, Aerospace

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Referring to statements made by the Secretary of Defense Robert Gates: "The secretary once again highlighted his ambitious next-year request for the more-versatile F-35s."[9]

- ^ "... noting that Raptors are ready for a mission around 62 percent of the time, if its low-observable requirements are met (DAILY, 20 November). Reliability goes up above 70 percent for missions with lower stealth demands."[172]

- ^ The F-22 was "lost" when a victim exited the area, regenerated and immediately re-engaged; the pilot had erroneously assumed it was still "dead".

- ^ Previous planning, as noted in 2006 Air Force news releases, appears to have seen the 531st Fighter Squadron take the active associate role, but this has now changed.[249]

- ^ empty weight+ 8,200 kg(fuel) + 1,142 kg (6 AMRAAM + 2 AIM-9X) + 292 kg (munition for the cannon)[281]

Citations[edit]

- ^ "Chronology of the F-22 Program." F-22 Team website, 4 November 2012. Retrieved: 23 July 2009.

- ^ a b Butler, Amy. "Last Raptor Rolls Off Lockheed Martin Line."[dead link] Aviation Week, 27 December 2011. Retrieved: 17 January 2012.

- ^ "Analysis of the Fiscal Year 2012 Pentagon Spending Request." COSTOFWAR.COM, 15 Februrar 2011. Retrieved: 31 August 2013.

- ^ "FY 2011 Budget Estimates." U.S. Air Force, February 2010. p. 1-15.

- ^ Reed, John. "Official: Fighters should be used for spying."Airforce Times, 20 December 2009. Retrieved: 9 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "F-22 Raptor fact sheet." U.S. Air Force, March 2009. Retrieved: 23 July 2009.

- ^ "Why F-22?". Lockheed Martin. Archived from the originalon 28 April 2009. Retrieved 10 November 2012.[dead link]

- ^ Houston, A. "Strategic Insight 9 – Is the JSF good enough?"Australian Strategic Policy Institute, 18 August 2004.

- ^ Baron, Kevin (16 September 2009). "Gates outlines Air Force priorities and expectations". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ a b Levine, Adam, Mike Mount and Alan Silverleib. "Gates Announces Major Pentagon Priority Shifts." CNN, 9 April 2009. Retrieved: 31 August 2011.

- ^ Serrie, Jonathan. (13 December 2011). "Last F-22 Raptor Rolls Off Assembly Line". Fox News. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ Sughrue, Karen (producer) and Lesley Stahl. "Is the Air Force's F-22 fighter jet making pilots sick?" 60 Minutes: CBC News, 6 May 2012. Retrieved: 7 May 2012.

- ^ Jenkins and Landis 2008, pp. 233–234.

- ^ Williams 2002, pp. 5–6.

- ^ "Fact sheet: Lockheed-Boeing-General Dynamics YF-22."U.S. Air Force, 11 February 2009. Retrieved: 18 June 2011.

- ^ Aronstein and Hirschberg 1998, p. 108.

- ^ Jenkins and Landis 2008, p. 234.

- ^ Goodall 1992, p. 110.

- ^ Miller 2005, p. 76.

- ^ Pearlstein, Steven and Barton Gellman. "Lockheed wins huge jet contract; Air Force plans to buy 650 stealth planes at $100 million each". The Washington Post, 24 April 1991.

- ^ Miller 2005, p. 65.

- ^ "F-22 Raptor Wins 2006 Collier Trophy." National Aeronautic Association. Retrieved: 23 July 2009.

- ^ a b c d Lopez, C.T. "F-22 excels at establishing air dominance." Air Force Print News, 23 June 2006. Retrieved: 23 July 2009.

- ^ Pace 1999, pp. 12–13.

- ^ "YF-22/F-22A comparison diagram." GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved: 13 June 2010.

- ^ "F-22 Partners."[dead link] NASA. Retrieved: 25 July 2009.

- ^ "F-22 weight increase agreed." Flight International, 3 May 1995.

- ^ Lobe, Jim. "New, Old Weapons Systems Never Die." Inter Press Service, 17 July 2009. Retrieved: 31 August 2011.

- ^ Kaplan, Fred "The Air Force tries to save a fighter plane that's never seen battle". Slate, 24 February 2009. Retrieved: 31 August 2011.

- ^ Younossi, Obaid et al. "Lessons Learned from the F/A–22 and F/A–18E/F Development Programs." RAND, 2005. Retrieved: 27 August 2011.

- ^ Sweetman, Bill. "Rivals Target JSF."[dead link] Aviation Week, 30 November 2010. Retrieved: 31 August 2011.

- ^ Herman, Arthur. "Don't let O disarm our military." New York Post, 10 January 2011. Retrieved: 31 August 2011.

- ^ Brumby, Otis, Bill Kinney and Joe Kirby. "Around Town: As the F 35 program revs up the F 22 ramps down." The Marietta Daily Journal, 6 June 2011. Retrieved: 31 August 2011.

- ^ a b Williams 2002, p. 22.

- ^ Grant, Rebecca. "Losing Air Dominance." Airforce Magazine, December 2008.

- ^ "Sticker Shock: Estimating the Real Cost of Modern Fighter Aircraft, p. 2." Defense-Aerospace.com, July 2006. Retrieved: 23 July 2009.

- ^ "Defense Acquisitions: Assessments of Selected Major Weapon Programs", p. 59. Government Accountability Office, 31 March 2006. Retrieved: 2 February 2008.

- ^ "FY 2009 Budget Estimates", p. 1–13. US Air Force, February 2008. Retrieved: 23 July 2009.

- ^ "Defense Acquisitions: Assessments of Selected Weapon Programs." United States Government Accountability Office, Report to Congressional Committees, March 2011.

- ^ Hennigan, W.J. "Air Force to modify F-22 following fatal crash." Los Angeles Times, 20 March 2012.

- ^ a b "Lockheed Martin Awarded Additional $5 Billion in Multiyear Contract to Build 60 F-22 Raptors" (Press release). Lockheed Martin. 31 July 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- ^ "US Department of Defense contracts." U.S. Department of Defense, 31 July 2007. Retrieved: 28 August 2011.

- ^ "HZ00295: Obey amendment overview." Library of Congress. Retrieved: 9 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Smith, R. Jeffrey. "Premier U.S. fighter jet has major shortcomings: F-22's maintenance demands growing." The Washington Post, 10 July 2009. Retrieved: 24 July 2009.

- ^ Bruno, M. "Appropriators Approve F-22A Multiyear, But Not Foreign Sales."[dead link] Aerospace Daily & Defense Report, 27 September 2006. Retrieved: 28 August 2011.

- ^ "H.R. 2647: National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2010 (overview)." U.S. House of Representatives viaOpencongress.org. Retrieved: 27 April 2012.

- ^ "H.R.2647 National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2010 (see Sections 1250 & 8056.)" Thomas.loc.gov.Retrieved: 26 September 2010.

- ^ Carmen, G. "Rapped in the Raptor: why Australia must have the best." The Age, 2 October 2006. Retrieved: 31 August 2011.

- ^ Kopp, Dr. Carlo. "Is The Joint Strike Fighter Right For Australia?"[dead link] Air Power Australia. Retrieved: 23 July 2009.

- ^ "Australia and the F22 Raptor." kuro5hin.org, 26 June 2006. Retrieved: 3 July 2006.

- ^ Landers, K. "Australia to buy 102 Lockheed jet fighters." The World Today, 27 June 2006.

- ^ Govindasamy, Siva. "Australia to weigh Lockheed Martin F-22 against Russian fighters."[dead link] Reed Business Information, Flightglobal.com, 10 January 2008. Retrieved: 2 February 2008.

- ^ "Australian minister says he wants option to buy US F-22 Raptor."[dead link] International Herald Tribune, 23 February 2008.

- ^ "RAAF JSF tech spec." U.S. Air Force. Retrieved: 27 April 2012.

- ^ "Israeli Plans to Buy F-35s Hitting Obstacles." Defense Industry Daily, 27 June 2006. Retrieved: 23 July 2009.

- ^ Bennet, J.T. "Air Force Plans to Sell F-22As to Allies."InsideDefense.com, 18 February 2006. Retrieved: 23 July 2009.

- ^ Konishi, Weston S. and Robert Dujarric. "Hurdles to a Japanese F-22." Japan Times, 16 May 2009. Retrieved: 3 August 2009.

- ^ "Japan prefers F-22 fighter over F-35". United Press International. 9 June 2009. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ^ Crimmins, Thomas. "How US deployment of the F-22 fighter, or its sale to Israel, could give nuclear diplomacy more time on Iran." Jerusalem Post, 19 March 2009.

- ^ Crimmins, Thomas. "F-22 Fighter Can Buy Time in Israel's Nuclear Showdown with Iran." Thecuttingedgenews.com, 23 March 2009. Retrieved: 9 May 2010.

- ^ Cohen, Ariel (20 January 2009). "Can the U.S. F-35 fighter destroy Russia's S-300 systems?". United Press International. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ GAO-06-455R "Tactical Aircraft: DOD Should Present a New F-22A Business Case before Making Further Investments."Government Accountability Office. Retrieved: 9 May 2010.

- ^ "Washington in Brief; Senators demand release of three F-22 reports." The Washington Post, 10 November 2007.

- ^ Sevastopulo, Demetri. "Lockheed Martin given F-22 reprieve."[dead link] Financial Times, 17 January 2008. Retrieved: 2 February 2008.

- ^ Lococo, Edmond and Tony Capaccio. "Pentagon Budget Means Cash for Lockheed and Northrop." Bloomberg, 9 January 2010. Retrieved: 28 August 2011.

- ^ Trimble, Stephen. "US Congress passes $487.7 defence spending bill, slashes aircraft." Flightglobal.com, 24 September 2008. Retrieved: 10 November 2012.

- ^ Wolf, Jim (12 November 2008). "Pentagon OKs funds to preserve F-22 line". Reuters. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- ^ Dimascio, Jen. "Defense cuts rolled back in House."politico.co, 18 June 2009. Retrieved: 23 July 2009.

- ^ "Transcripts."[dead link] U.S. Senate, Committee on Armed Services, 9 July 2009.

- ^ http://www.hatch.senate.gov/public/_files/USAFResponse.pdf

- ^ Thomas "S.AMDT.1469 to cut F-22 funding."Thomas.loc.gov. Retrieved: 13 June 2010.

- ^ Matthews, William. "Senate Blocks Funds For More F-22s, But Battle's Not Over." Defense News, 21 July 2009. Retrieved: 23 July 2009.

- ^ Gates, Robert (16 July 2009). Economic Club of Chicago(Speech). Economic Club of Chicago. Chicago, Illinois: US Department of Defense. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ Kreisher, Otto. "General: Air National Guard needs new fighter jets." CongressDaily, 29 July 2009. Retrieved: 3 August 2009.

- ^ Matthews, William. "House Reverses Itself, Votes To Kill F-22 Buy." Defense News, 31 July 2009.

- ^ "CRS RL31673 Air Force F-22 Fighter Program: Background and Issues for Congress, p. 15." Assets.opencrs.com. Retrieved: 26 September 2010.

- ^ Rosenwald, Michael S. "Senate votes to stop making more F-22 Raptor fighter jets." The Los Angeles Times, 22 July 2009. Retrieved: 28 August 2011.

- ^ Lubold, Gordon. "When Gates stared down the F-22 lobbyists. To cut the costly F-22 Raptor, he had to fire two top Air Force officials in his way." csmonitor.com, 28 September 2009. Retrieved: 28 August 2011.

- ^ "RAND: Ending F-22A Production: Costs and Industrial Base Implications of Alternative Options." rand.org. Retrieved: 26 September 2010.

- ^ a b Wolf, Jim (12 December 2011). "U.S. to mothball gear to build top F-22 fighter". Reuters. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ Trimble, Stephen (5 March 2010). "USAF considers options to preserve F-22 production tooling". Flightglobal. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ Trimble, Stephen. "For posterity, Lockheed creates F-22 'how-to' manual." The DEW Line, 3 November 2010.

- ^ Axe, David. "Fixing Worn-Out Raptors at Hill Air Force Base." offiziere.ch, 4 August 2012.

- ^ Wolf, Jim (18 June 2009). "UPDATE 4-Top general warns against ending F-22 fighter". Reuters. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ Gertz, Bill. "China's stealth jet coming on, Gates confirms."The Washington Times, 9 January 2011. Retrieved: 31 August 2011.

- ^ Butler, Amy. "Last Raptor Rolls Off Lockheed Martin Line."[dead link] Aviation Week, 27 December 2011.

- ^ "F-22 aircraft No. 4005 completes successful first flight."Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved: 23 July 2009.

- ^ "DOT&E FY2013 Annual Report - F-22A Advanced Tactical Fighter"

- ^ Reyes, Delos Julius (6 October 2009). "F-22 Raptor team receives AFMC award". US Air Force. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ^ "GAO-10-388SP, Defense Acquisitions: Assessments of Selected Weapon Programs." Government Accountability Office, 30 March 2010. Retrieved: 26 September 2010.

- ^ Majumdar, Dave (23 March 2012). "USAF fields first upgraded F-22 Raptors". Flightglobal. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ Majumdar, Dave. "Limitations keep F-22 from use in Libya ops." Airforce Times, 22 March 2011. Retrieved: 31 August 2011.

- ^ Trimble, Stephen (1 January 2009). "USAF deploys Global Express jet with new Northrop relay suite". Flightglobal. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ Sirak, Michael C. "Daily Report Friday 26 March 2010." Air Force magazine. Retrieved: 5 April 2010.

- ^ Young, John J. Jr. "Defense Writers Group transcript, p. 15." Air Force magazine, 20 November 2008. Retrieved: 26 September 2010.

- ^ Tirpak, John A. "Fighter of The Future." Air Force magazine. Retrieved: 23 July 2009.

- ^ Trimble, Stephen (2 February 2011). "USAF invites rivals to break Lockheed's grip on F-22 upgrade work". Flightglobal. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ "Department of Defense contracts."

- ^ Burnett, Richard. "Lockheed defense deals prevail despite budget crunch." Orlando Sentinel, 12 December 2011.

- ^ Sullivan, Michael J. "GAO-12-447, F-22A Modernization Program Faces Cost, Technical, and Sustainment Risks."GAO, 2 May 2012.

- ^ Trimble, Stephen. "Lockheed proposes F-35'ing the F-22."The DEW Line, 29 October 2010. Retrieved: 31 August 2011.

- ^ Majumdar, Dave. "Raptor to use F-35 radar absorbent coatings." Airforce Times, 6 April 2011. Retrieved: 31 August 2011.

- ^ Majumdar, Dave. "Cost, risk scuttle planned Raptor data upgrade." Airforce Times, 31 March 2011. Retrieved: 31 August 2011.

- ^ Majumdar, Dave (30 May 2011). "F-22 Getting New Brain".Defense News. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ "Missile Launch Detector (MLD)". Lockheed Martin. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ^ Eshel, Tamir. "First Raptor Supersonic AIM-9X Launch."Defense Update, 8 August 2012.

- ^ Majumdar, Dave (11 March 2013). "USAF to evaluate Scorpion helmet display on F-22 Raptor". Flightglobal. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ Majumdar, Dave (11 April 2013). "F-22 helmet-display demonstration, possibly a casualty of sequestration".Flightglobal. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ Stein, Keith. "Cost concerns over F-22 Raptor modernization plan." The Examiner, 27 April 2012.

- ^ Majumdar, Dave."Lockheed awarded $6.9 billion F-22 upgrade contract." FlightGlobal.com, 21 February 2013.

- ^ Majumdar, Dave (6 August 2012). "First supersonic AIM-9X launch from an F-22 Raptor". Flightglobal. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ Rector, Gene. "Officials: No 'smoking gun' uncovered but changes will make F-22 safe to fly." The Warner Robins Patriot, 24 February 2012.

- ^ Majumdar, Dave (8 January 2013). "USAF to field F-22 life support mods this January". Flightglobal. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ^ Gertler, Jeremiah. "Air Force F-22 Fighter Program." CRS RL31673, 25 October 2012.

- ^ Rolfsen, Bruce. "F-22 design problems force expensive fixes." Airforce Times, 12 November 2007.

- ^ Trimble, Stephen. "Boeing plots return to next-generation fighter market." Flight Global, 7 May 2010.

- ^ Carlson, Maj. Gen. Bruce. "Subject: Stealth Fighters." U.S. Department of Defense Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Public Affairs) News Transcript. Retrieved: 28 August 2011.

- ^ Boettcher, Daniel. "US shows off new Raptor jet." BBC, 11 July 2008. Retrieved: 31 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d Ayton, Mark. "F-22 Raptor". AirForces Monthly, August 2008, p. 75. Retrieved: 19 July 2008.

- ^ Powell, 2nd Lt. William. "General Jumper qualifies in F/A-22 Raptor." Air Force Link, 13 January 2005. Retrieved: 31 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fulghum, D.A. and M.J. Fabey. (online subscription version) "Turn and Burn."[dead link] Aviation Week, 8 January 2007. Retrieved: 7 November 2009.

- ^ "Lockheed Martin Recognized For Excellence In F-22 Raptor Sustainment" (Press release). Lockheed Martin. 9 December 2008. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ F-22 Materials and Processes

- ^ "F-22 v F-35 Comparison."[dead link] Air Force Association. Retrieved: 7 November 2009.

- ^ Kopp, Carlo. "Just how good is the F-22 Raptor: Carlo Kopp interviews F-22 Chief Test Pilot, Paul Metz." Air Power Australia. Retrieved: 10 November 2012.

- ^ Peron, L. R. "F-22 Initial High Angle-of-Attack Flight Results."(Abstract)." Air Force Flight Test Center. Retrieved: 7 November 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Fulghum, D.A and M.J. Fabey. "F-22: Unseen and Lethal: Raptor Scores in Alaskan Exercise" (online edition)."[dead link] Aviation Week. 8 January 2007. Retrieved: 28 August 2011.

- ^ Bedard, David. "Bulldogs accept delivery of last Raptor."Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson Public Affairs, 11 May 2012.

- ^ a b "USAF Factsheets F-22 Raptor." USAF, 8 May 2012.

- ^ Tirpak, John A. "Airpower, led by the F-22, can 'kick the door down' for the other forces." Airforce Magazine, March 2001.

- ^ Grant, Rebecca. "Why The F-22 Is Vital Part 13." UPI, 31 March 2009.

- ^ Klass, Philip J. "Sanders Will Give BAE Systems Dominant Role in Airborne EW." Aviation Week, Volume 153, issue 5, 31 July 2000, p. 74.

- ^ a b c Sweetman 2000, pp. 41–47.

- ^ "JSF-Raptor Radar Can Fry Enemy Sensors."defensenews.com. Retrieved: 7 November 2009.Retrieved: 7 November 2009.

- ^ "F-22 Raptor". Lockheed Martin. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ^ "Defense Science Board report on Concurrency and risk of the F-22 program." Dtic.mil, April 1995. Retrieved: 31 August 2011.

- ^ Pace 1999, p. 58.

- ^ Page, Lewis. "F-22 superjets could act as flying Wi-Fi hotspots." The Register, 19 June 2007. Retrieved: 7 November 2009.

- ^ Philips, E.H. "The Electric Jet." Aviation Week, 5 February 2007.

- ^ Thompson, Mark. "Defense Secretary Gates Downs the F-22." Time, 22 July 2009. Retrieved: 27 March 2010.

- ^ Wynne, Michael. "Michael Wynne on: The Industrial Impact of the Decision to Terminate the F-22 Program." Second Line of Defense. Retrieved: 31 August 2011.

- ^ Riley, Michael; Elgin, Ben (2 May 2013). "Business Week: China Cyberspies Outwit U.S. Stealing Military Secrets".Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ a b Williams 2002, p. 10.

- ^ Goebel, Greg. "The Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor."airvectors.net, 1 July 2011. Retrieved: 10 November 2012.

- ^ "Lockheed Martin’s Affordable Stealth". Lockheed Martin. 15 November 2000. p. 2.

- ^ Kopp, Carlo. "~Just How Good Is The F-22 Raptor?""Australian Air Power", September 1998.

- ^ "F-22s Won’t Get F-35 Datalinks,Yet" DoDBuzz, 31 March 2011

- ^ "Limitations keep F-22 from use in Libya ops."AirForceTimes, 22 March 2011.

- ^ AirForces Monthly, August 2010, p. 56.

- ^ "Military Avionics Systems", Ian Moir and Allan Seabridge, Wiley, pp. 360

- ^ a b c Williams 2002, p. 11.

- ^ "ACES ll® Ejection Seat Programs"[dead link] Goodrich.

- ^ "A preliminary investigation of a fluid-filled ECG-triggered anti-g suit", February 1994

- ^ Majumdar, Dave. "Sources: Bleed-air issue led to Raptor crash." Air Force Times, 8 September 2011.

- ^ Pace 1999, pp. 65–66.

- ^ "Technologies for Future Precision Strike Missile Systems – Missile/Aircraft Integration." Handle.dtic.mil. Retrieved: 26 September 2010.

- ^ "LAU-142/A AMRAAM Vertical Eject Launcher AVEL."[dead link] es.is.itt.com. Retrieved: 7 November 2009.

- ^ Staff (13 October 2013). "The F-22 Raptor: Program & Events". Defense Industry Daily. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ Polmar 2005, p. 397.

- ^ Miller 2005, p. 94.

- ^ DeMarban, Alex. "Target-towing Cessna pilot unconcerned about live-fire practice with F-22s." Alaska Dispatch, 3 May 2012.

- ^ "F-22 vs F-35 Comparison."[dead link] Air Force Association.

- ^ "USAF Almanac." Air Force magazine, May 2006.

- ^ "U.S. orders two dozen raptors for 2010". United Press International. 22 November 2006. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ Gottliebsen, Robert (5 March 2013). "Stephen Smith's 11th-hour flight option". Business Spectator. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ Pace 1999, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Tirpak, John A. "The Raptor as Bomber." Air Force magazine, January 2005. Retrieved: 25 July 2009.

- ^ a b "F-22 Stealth." GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved: 21 February 2007.

- ^ Trimble, Stephen (16 July 2008). "Russia's views about the new F-22 flying display". Flightglobal. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d Fulghum, David A. "Away Game" Aviation Week. 8 January 2007. Retrieved: 25 July 2009.

- ^ Fulghum, David A. "F-22 Raptor To Make Paris Air Show Debut"[dead link] Aviation Week, 4 February 2009. Retrieved: 15 February 2009.

- ^ Butler, Amy. "USAF Chief Defends F-22 Need, Capabilities."[dead link] Aviation Week, 17 February 2009. Retrieved: 31 August 2011.

- ^ Sprey, Pierre. "Interview," 22 June 2008.

- ^ Weiner, Tim. Blank Check: The Pentagon's Black Budget. New York: Warner Books, 1990. ISBN 978-0-44639-275-4.

- ^ Grant, Rebecca. "The Radar Game."[dead link] Mitchell Institute, 2010. Retrieved: 31 August 2011.

- ^ "Analogues of Stealth." Northrop Grumman. Retrieved: 27 April 2012.

- ^ "Military Aircraft Names." Aerospaceweb.org. Retrieved: 26 September 2010.

- ^ "U.S. to Declare F-22 Fighter Operational." Agence France-Presse, 15 December 2005.

- ^ John Pike. "F-22 Flight Test". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2013-11-16.

- ^ "F-22 Milestones - Part 2". Code One Magazine. Retrieved 2013-11-16.

- ^ 7 May 2013 (2013-05-07). "Raptor 4007 starts testing Inc 3.2A upgrade on its 1000th sortie". Flightglobal.com. Retrieved 2013-11-16.

- ^ "F-22 design problems force expensive fixes". Air Force Times, 12 November 2007. Retrieved: 17 February 2014.

- ^ "Flaw Could Shorten Raptors' Lives." News Herald (Panama City, FL), 4 May 2006. Retrieved: 12 February 2014.

- ^ "F-22A Raptor goes operational". US Air Force. 15 December 2005. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ Schanz, Marc V. "Aerospace World: Red Flag Raptors." Air Force magazine, May 2007. Retrieved: 9 February 2008.

- ^ "F-22 Squadron Shot Down by the International Date Line."Defense Industry Daily, 1 March 2007. Retrieved: 5 February 2014.

- ^ Johnson, Maj. Dani (19 February 2007). "Raptors arrive at Kadena". US Air Force. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ "Raptors Perform First Intercept of Russian Bombers." Air Force magazine, Daily Report, 14 December 2007. Retrieved: 9 May 2010.

- ^ "Russian Air Force denies it violated British airspace". RIA Novosti. 25 March 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ Hopper, David (12 December 2007). "F-22s at Langley receive FOC status". US Air Force. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ Schultz, 2nd Lt. Georganne E. "Langley earns 'excellent' in ORI." F-16.net, 22 April 20078. Retrieved: 9 May 2010.

- ^ "Air Force World." Air Force magazine, July 2008, Vol. 91, No. 7, p. 20.

- ^ Clark, Colin. "Gates Opposed AF Plans to Deploy F-22 to Iraq." DOD Buzz, 30 June 2008. Retrieved: 31 August 2011.

- ^ Thompson, Mark (17 April 2011). "The Strange Case of the (Nearby) But Missing F-22s Over Libya". Time. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ Cenciotti, David (30 September 2013). "Rapid Raptor Package: US Air Force’s New Concept For Deploying Four F-22 Stealth Fighters In 24 Hours". www.businessinsider.com. The Aviationist. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- ^ "Rapid Raptor Package."

- ^ Delos Reyes, Julius. "Edwards F-22 Raptor performs aerial refueling using synthetic fuel." Desert Eagle, 3 September 2008, via F-16.net. Retrieved: 14 September 2011.

- ^ Quick, Darren. "F-22 Raptor hits Mach 1.5 on camelina-based biofuel." Gizmag, 23 March 2011.

- ^ "US Deployment near Iran". Fox News. 27 April 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ "Iran: US stealth fighter deployment to UAE harmful". Fox News. 30 April 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ^ Holloman F-22s Return from Middle East - Airforcemag.com, February 1, 2013

- ^ F-22 Flew to Drone's Rescue off Iran Coast - Military.com, 17 September 2013

- ^ "12 F-22 Raptors deployed to Japan." Airrecognition.com, 14 January 2013.